How the most progressive retailers are driving positive impact in society.

Many retail businesses have rightly begun to prioritise critical social issues such as environmental sustainability and inclusion and diversity. As a design consultancy focused on physical spaces, we have worked with clients and written about these issues. The true impact of retail stores - and the influence of retail businesses - extends far beyond the above issues. This influence has become increasingly evident as we saw during the pandemic as restrictions forced stores to temporarily close, reducing once bustling city high streets and local villages into ghost towns. Only once stores closed did we recognise the true value of retail in our lives.

One element of retail that remained constant was the ability to purchase products (albeit online and delivered to our homes). We’d taken retail for granted, forgetting its purpose as a stage for culture and creativity, a place for community and social contact, and its role as an employer. These are the elements we wish to bring into focus.

Retail is a microcosm of society. The prominence of the retail industry means it has an ability (perhaps even a duty) to tackle more significant social problems and influence lasting change. In highlighting the true impact that retail has, we hope to inspire retailers to use their stores as a positive force for society, and in doing so, forge deeper relationships with customers. Such a reconfiguration of perspective, and perhaps priorities, will benefit customers and businesses alike. It will not just improve the perception of an individual store, but of the brand too.

Retail transforms and defines communities

At the heart of most European cities and towns, you will find a church. The central location of these churches is symbolic of their role in society, as a focal point that binds the community. In today’s society, places of religious worship are less of a focal point and have been largely replaced by retail as the place for social gathering. The modern American mall is often the centre point of the town. The local row of shops is often the main artery of a British village, and the modern town square no longer sits aside a cathedral but is encircled by retail stores.

Retail stores are critical to revitalising urban locations, helping stimulate local economies and social integration. A great example of this is King’s Cross in central London. The once industrial area has been successfully regenerated into a mixed-use development of residential property, commercial offices, educational campuses, hospitality and retail. At the heart of the redevelopment is Coal Drops Yard, a shopping destination that demonstrates the transformative qualities of retail. Most importantly, it creates a focal point of culture and commerce, a place for social interaction connecting surrounding offices, transport hubs and the broader city.

Whilst King’s Cross is an example of large-scale regeneration, retail can also influence change at a much smaller scale. Even a single retail store can have transformative value. Local areas are often defined by the types of stores they host. Having a brand flagship or a destination store can change how people view that area. The brand’s investment is a symbolic endorsement of the locale, and while it’s likely to be a strategic decision to open a store in a specific location, a brand doesn’t always reflect on the transformative effect of its choice.

The power of modern brands is such that they can define, or redefine, an area through their existence. Suppose a brand opens a flagship store in a traditionally undesirable area with the intent to regenerate it. The investment might return to them two-fold, creating a wave of devoted local customers and brand ambassadors. It’s also likely that other retailers will follow their lead, and new customers will be attracted from outside the area, having a further positive effect on the local community. Starbucks Community Stores are a great example of retail designed to lift disadvantaged areas by providing local jobs and an aspirational place to meet. Similarly, Footlocker Power Stores are committed to hiring staff that live locally. The proof of their investment will come to fruition in future years, but it would be great to see other brands follow their lead.

The store’s greatest value is as a social space

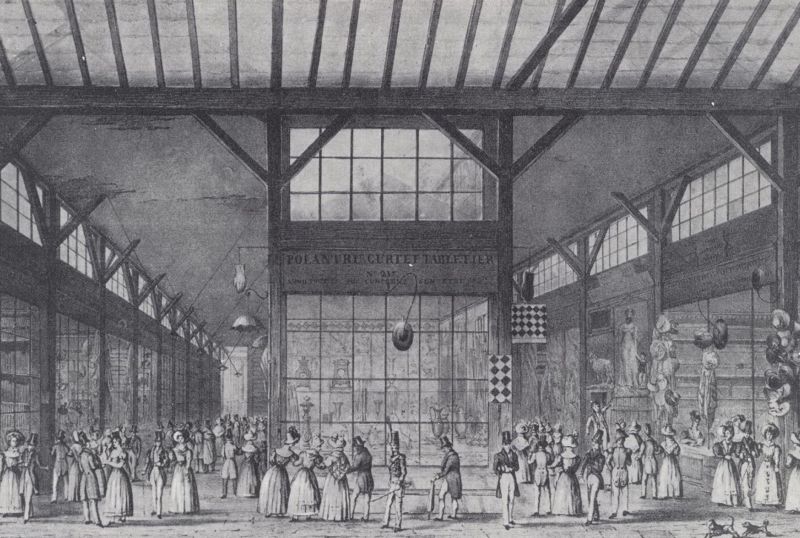

The oldest example of retail (that bears any resemblance to modern retail) would be an ancient Greek agora. Located in the city centre, these were gatherings of traders and merchants. People would shop but also socialise and participate in discussions concerning wider society. Fast forward more than two thousand years to the earliest iteration of the modern shopping centre. Wealthy French middle-class would stroll down the arcade of the Galeries de Bois in Paris, admiring high-priced items displayed behind glass. Some people would purchase, but it was predominantly a place to be seen and to socialise away from the dirty streets.

If we strip retail down to its bare essence, it is less a place to purchase and more a social pastime. In their strive for commercial success, retailers have lost sight of this over the last few decades. Yet recent trends are shifting retail back to its original core purpose. Firstly, the emergence of e-commerce has begun to free the physical store of its core duty to facilitate transactions. The resulting emergence of experiential retail is a modern adaptation of its original social and communal role; shopping is a past-time we use to escape, discover, and learn. Secondly, the pandemic stripped societies around the world of all social interaction, revealing our true dependency on physical retail to fulfil this basic need. This new-found awakening is something that retail businesses must react to now; stores are a social space that can energise and revitalise society.

For many, an interaction with the postman, the butcher or a local grocer is an important feature of social normalcy and may be considered akin to participating in society. As populations age, opportunities for social activities often reduce, as hospitality and cultural events are often dominated by youth. Retail experiences could emerge as a predominant form of leisure among older generations and, as a by-product, create feelings of social integration. With this in mind targeting older generations in physical retail might be a great social cause with far-reaching benefits. It might also be an astute commercial decision to target this group, given their purchasing power and leisure time.

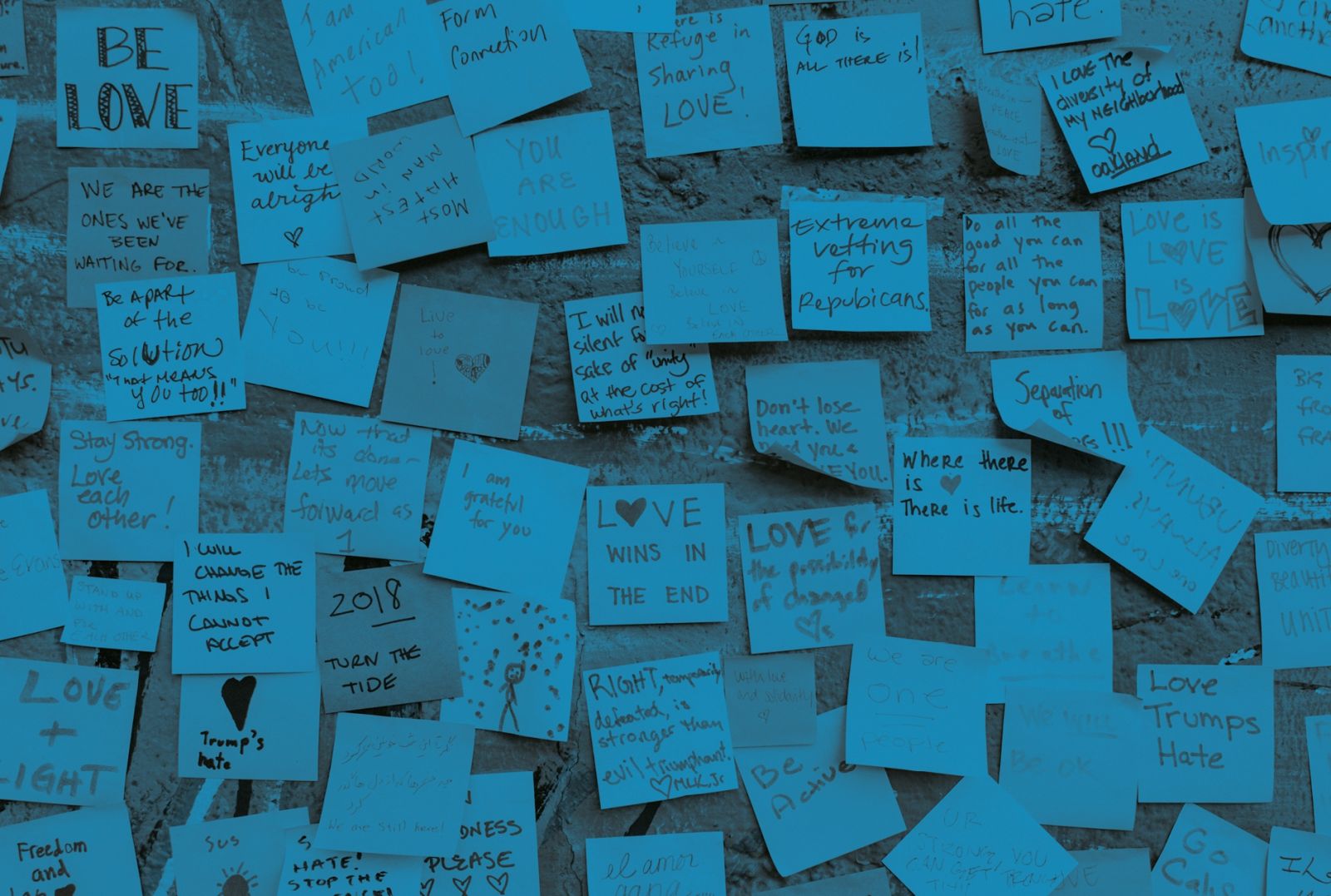

For modern brands hoping to captivate younger consumers, the social nature of retail has a different face. The growth of branded social experiences is a reflection of this. A yoga class at Lululemon, or a drawing class at Apple leverage the physical store, naturally bringing people together and creating a sense of community. For younger generations, retail might also need to reflect the social landscape outside of the physical retail store.

At a time when social media is entrenched in the culture of social interactions, it makes sense that the emergence of retail stores as social spaces for these younger generations involves integration between social media platforms and the physical environment. Burberry’s ‘social retail store’ in Shenzhen does just that. Using a custom WeChat mini programme, customers explore and engage with the store, generating ‘social currency’. This is one of the new realities of physical stores being social spaces. The union between phones and stores is currently focused on marketing and sales. While a truly social experience will utilise phones to encourage peer-to-peer interaction within the physical store. Engaging and socialising younger consumers digitally in this way embeds them more firmly into their ‘tribe’, ultimately generating a deeper loyalty to the brand.

Staff are the custodians of change

In the UK, retail is the largest private-sector employer with 2.9 million workers, while in the US, the sector employs over 15 million staff. Whether it’s supermarkets, telco or clothing stores, there are few workers people encounter more often than retail staff. The importance of staff in our shopping experience is evident. 71% of customers say store staff have a significant impact on their experience. They’re also highly regarded brand ambassadors. Customers are 2.6 times more likely to recommend a business after interacting with an engaged member of staff. Yet their importance in society has been greatly undervalued. The nature of their social reach means that encounters with happy, motivated staff can potentially create a significant positive ripple effect across our wider society.

When the UK plunged into its first major national lockdown due to the pandemic, there was a change in the way retail staff were perceived. Supermarket staff re-stocking shelves were seen as ‘front-line’ workers. A job rarely associated with significant social importance was re-interpreted as critical to a functioning society.

Central to maximising retail’s impact on society is how we value and treat retail staff. Retail has always been about people. If we analyse the broader value of each staff member, we get a glimpse into the greater value of the industry. Retail staff are more than shelf-stackers and cashiers. On many levels, they are educators and advisers. They need to be knowledgeable but also patient and empathetic. We need retail staff to understand the importance of every moment of social interaction. They may offer the only moment of social interaction for a customer on that day. Staff need to understand when elderly customers need help or how an autistic or disabled customer might have different needs. Such a complicated melting pot of required skillsets would present a recruitment challenge for any industry. With this in mind, retail staff must be treated with respect and regarded as experts.

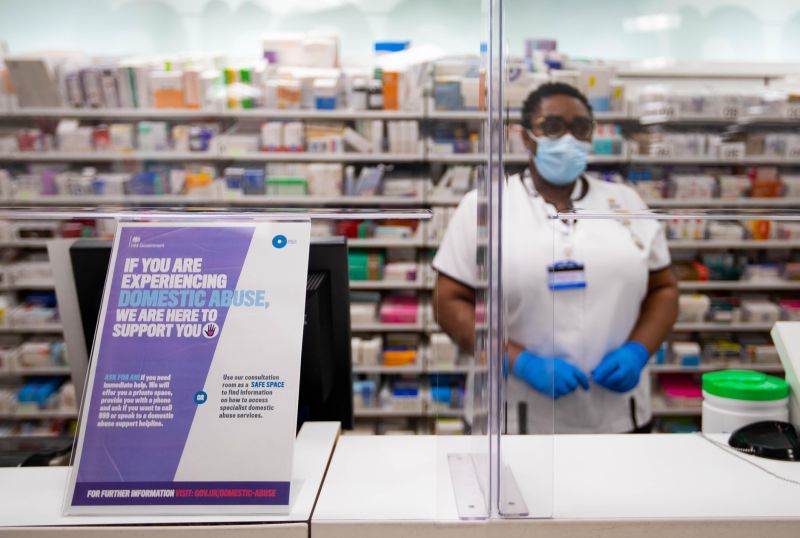

As the public face of the brand, retail staff are the people that need to embody a brand’s involvement in social causes. In light of social movements related to protecting women against violence, several British supermarkets (Tesco, Asda, Morrisons and Marks & Spencer) have advertised their premises as ‘safe spaces’, effectively designating their stores as places of refuge for people who fear for their safety. A year earlier, British supermarket Morrisons and pharmacy chain Boots announced their stores as places for victims of domestic violence to seek refuge and contact social services. The British government also collaborated with Boots and other independent pharmacies to launch a code-word scheme, ‘Ask for ANI’ (Action Needed Immediately), allowing victims to discreetly alert staff to their need for help.

These initiatives are an example of the potential capacity that retail stores and their staff have to influence a community and its wellbeing. Initiatives like these instantly re-frame the role of supermarket and pharmacy staff. Attending to domestic violence victims is normally handled by counsellors or police with specialised training - this is now becoming the remit of store staff, who must be trained to deal with these situations. Expanding their roles in such ways should surely elevate their status.

Retail’s role in reducing collective stressors

One delayed morning train can cause moments of emotional tension across hundreds of people's workspaces. Retail experiences have a less obvious but similar capacity. Negative moments caused by ineffective communication or a poorly designed in-store service can easily create inconvenience and aggravation.

The store can be a setting for tension and stress, or moments of discrimination and exclusion. What needs to be understood is that our experiences in retail are so frequent that their cumulative effect can often impact our day-to-day mood. Consider how security protocols have an impact on the psyche of the local shoppers. Retail brands commonly understand that staff interactions are symbols of how a retail brand values its local customers. What needs far greater consideration is how experiences in retail impact how customers view themselves. It may be easy for retailers to underestimate the impact of one moment within a store. A single act of discrimination inside a store, such as unnecessary security checks, might be deeply uncomfortable in the moment it happens, but it can also leave a lasting and traumatic impression.

Retailers need to take ownership of their role in the broader experience of local communities. Designing stores without friction is often a thankless endeavour. When something works, it is just ‘how it should be’, going unnoticed and rarely receiving praise. Yet positive moments, reducing stress, can contribute to an accumulated experience of society; this should not be lost on retail businesses striving to provide ‘frictionless’ experiences. In contrast to a delayed train, an innovation improving the experience of parking or payment can improve experiences beyond that moment.

Conclusion

Retail is so interwoven with society that it has the potential to significantly influence our well-being. In our daily lives, we might have several retail interactions; visiting a coffee shop in the morning, a bank during a lunch break, a clothing store after work, followed by a supermarket before going home. Friction in these moments accumulates and contributes to our collective experience over a day, a week, or a month. In much the same way, good experiences can have an equally positive effect. The moments of human kindness, the excitement, discovery, or the delight in learning something new. In this sense, what is the true value of a well-designed retail experience? It is so much more than selling a product or connecting with a customer. Good retail design involves considering your location and how you contribute to the surrounding community, creating an accessible, cultural and social space. Good retail design is not just about providing positive experiences but ensuring there are no moments of negative friction and understanding its impact on both an individual and on the community.